Lasten ja nuorten energiajuomien käyttö on yleistynyt – yhteys suositusten vastaiseen yöunen pituuteen

Lähtökohdat Lasten ja nuorten energiajuomien käytöstä ja siihen liittyvistä tekijöistä on Suomessa niukasti seurantatietoa. Käyttöön liittyy epäsuotuisia terveysvaikutuksia, eikä juomia suositella lapsille ja nuorille niiden korkean kofeiinipitoisuuden vuoksi.

Menetelmät Tutkimuksessa tarkasteltiin kuvailevilla analyyseillä ja logistisilla sekamalleilla 11-, 13- ja 15-vuotiaiden energiajuomien käyttöä, sen ajallista muutosta sekä yhteyksiä sosiodemografisiin tekijöihin ja unisuosituksen toteutumiseen. Kansallisesti edustava aineisto perustuu vuosien 2014, 2018 ja 2022 WHO-Koululaistutkimukseen (n = 15 171).

Tulokset Vuodesta 2014 vuoteen 2022 energiajuomien käyttö yleistyi kaikissa ikäryhmissä. Erityisesti useita kertoja viikossa tapahtuva käyttö lisääntyi huomattavasti. Ikäryhmien väliset erot kasvoivat ja sukupuolten välinen ero kaventui. Käyttö oli yleisempää nuorilla, joilla ikäryhmän mukainen yöunen pituussuositus ei täyttynyt, sekä vuonna 2022 nuorilla, joilla perheen varallisuus oli korkeampi.

Päätelmät Lasten ja nuorten energiajuomien käyttö on yleistynyt. Käytöstä tarvitaan lisää tietoa terveiden elintapojen edistämiseksi sekä nykyisten toimenpiteiden vaikuttavuuden arviointia ja terveyspoliittista päätöksentekoa varten.

Lasten ja nuorten energiajuomien käyttö on todettu potentiaaliseksi kansanterveydelliseksi uhkaksi (1). Siihen kytkeytyy monia epäsuotuisia terveysvaikutuksia, kuten sydän- ja verenkiertoelimistön oireet, esimerkiksi verenpaineen nousu, sykkeen muutokset ja sydämentykytys) (2), unihäiriöt, esimerkiksi lyhyt unen pituus (3,4,5,6,7), myöhäinen nukkumaanmenoaika tai yöllinen heräily (8), erilaiset psyykkiset ja somaattiset oireet (2,5,8) sekä heikko koettu terveys (7).

Nämä vaikutukset liittyvät erityisesti energiajuomien korkeaan kofeiinipitoisuuteen (9), jolle ei ole kyetty luotettavasti määrittämään turvallisen saannin raja-arvoa tälle väestöryhmälle (10).

Suomessa energiajuomien käyttöä on pyritty hillitsemään Valtion ravitsemusneuvottelukunnan ja Terveyden ja hyvinvoinnin laitoksen suosituksilla, jotka koskevat alle 15-vuotiaita (11,12). Suosituksista huolimatta energiajuomien käyttö on yleistä. Vain joka toinen 13- ja 15-vuotias raportoi vuonna 2022, ettei käytä niitä (13).

Euroopan elintarvikeviranomainen on suositellut energiajuomien käytön kasvun seuraamista jo vuonna 2013 (14). Suomessa on kuitenkin niukasti seurantatietoa lasten ja nuorten energiajuomien käytön yleisyydestä ja käyttöön yhteydessä olevista tekijöistä etenkin alakouluikäisiltä.

Tässä tutkimuksessa kuvaamme 11-, 13- ja 15-vuotiaiden energiajuomien käyttöä vuosina 2014, 2018 ja 2022. Lisäksi tarkastelemme iän, sukupuolen, perheen varallisuuden ja ikäryhmän mukaisen yöunen pituussuosituksen toteutumisen (15) yhteyksiä energiajuomien käyttöön sekä yhteyksien muutosta vuosien välillä.

Yöunen pituuden yhteyttä energiajuomien käyttöön tarkasteltiin aiemmin (7,8,16) havaitun keskinäisen mutta kansallisesti vähän tutkitun yhteyden vuoksi.

Menetelmät

Tutkimuksen poikkileikkausaineisto koostuu kansallisesti edustavan WHO-Koululaistutkimuksen (HBSC-study) vuosien 2014, 2018 ja 2022 kyselyaineistoista (n = 15 171, 50,2 % poikia; vastaajien vuosittainen vaihteluväli n = 3 408–7 925). Tutkimusaineisto kattaa 11-, 13- ja 15-vuotiaat, jotka edustavat luokkatasoja 5., 7. ja 9.

Otanta toteutettiin jokaisena aineiston keruuvuotena erikseen Tilastokeskuksen ylläpitämästä oppilaitosrekisteristä. Osallistuvat koulut valittiin ositetulla ryväsotannalla, jolla taattiin maantieteellinen ja asuinkuntamuotoinen edustavuus. Otantayksikkönä käytettiin koulua, jonka valintatodennäköisyys oli suhteutettu sen kokoon. Osallistuvat luokat otoskoululla arvottiin.

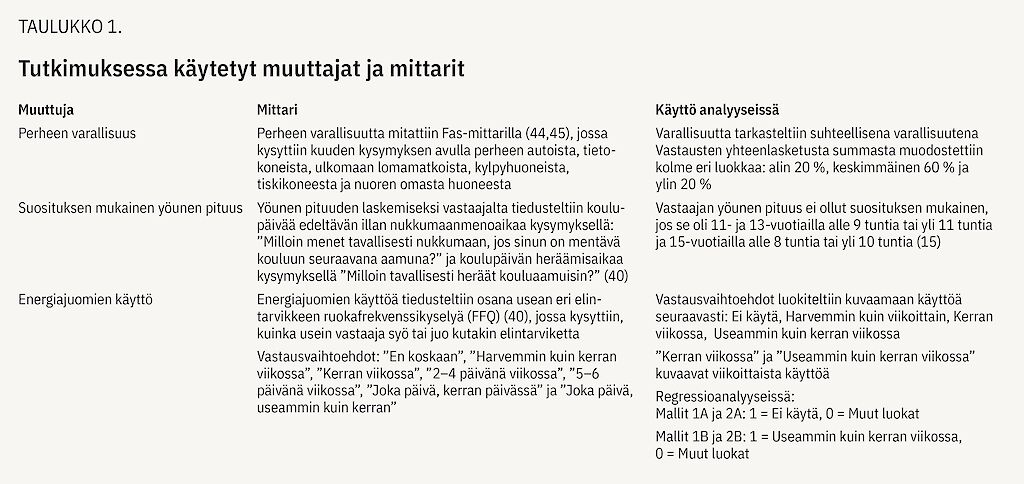

Vuoden 2014 aineisto kerättiin paperisin kyselylomakkein ja vuosien 2018 ja 2022 aineistot sähköisesti Webropol-kyselyohjelmalla. Tutkimukseen osallistuminen oli vapaaehtoista, ja kyselyyn vastattiin nimettömästi. Iän ja itseraportoidun sukupuolen lisäksi tutkimuksessa käytettiin taulukossa 1 kuvattuja muuttujia.

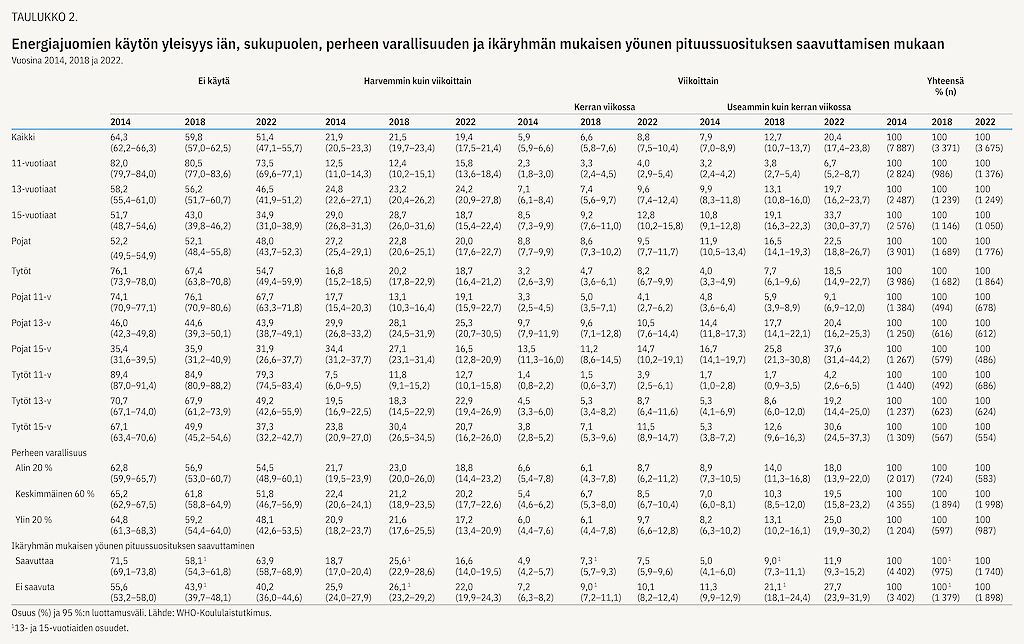

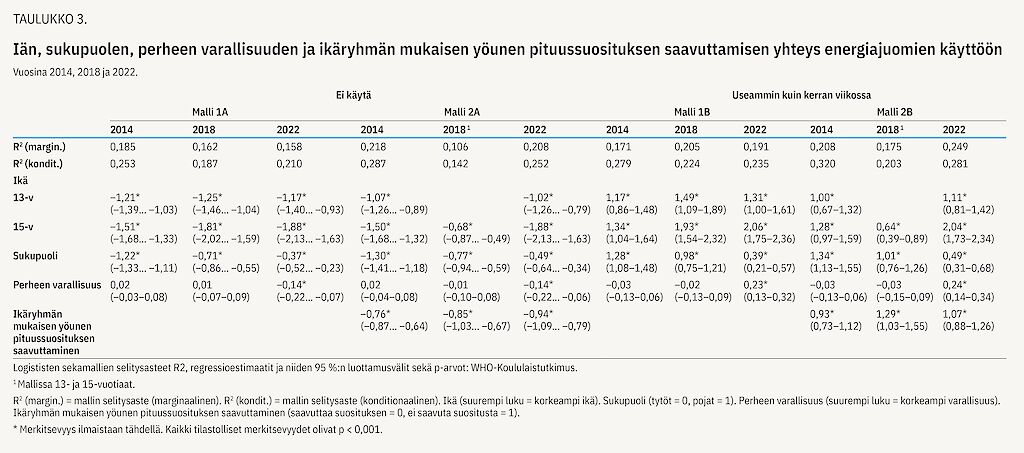

Tilastoanalyyseissä laskettiin Stata (versio 18) -tilasto-ohjelmistolla otantamenetelmäkorjatut ja painotetut prosenttiosuudet ja niiden 95 %:n luottamusvälit energiajuomien käytölle eri taustamuuttujien suhteen (taulukko 2). Regressiomalleissa (taulukko 3) sovitettiin kaksi eri mallia jokaiselle vuodelle erikseen.

Ensimmäisissä malleissa huomioitiin ikä, sukupuoli sekä perheen varallisuus. Toisiin malleihin lisättiin näiden lisäksi suosituksen mukainen yöunen pituus. Vuoden 2018 kohdalla toisessa mallissa ei ollut mukana 11-vuotiaita, sillä unen pituutta ei kysytty heiltä kyseisenä ajankohtana.

Malleissa otettiin huomioon satunnaismuuttujalla aineiston klusterointi koulutasoittain. Mallien regressioestimaatteja voi verrata vuosien välillä keskenään tutkimalla 95 %:n luottamusvälien leikkauskohtia.

Malleissa jatkuvat muuttujat standardoitiin keskiarvon ja keskihajonnan suhteen. Lisäksi malleille laskettiin sekä marginaaliset että konditionaaliset R2-arvot (17). Sekamalleissa marginaalinen R2 viittaa selitysasteeseen, jossa otetaan huomioon vain selittäjämuuttujat, ja konditionaalinen huomioi edellisten lisäksi koulutason satunnaisvaikutuksen.

Regressiomallit muodostettiin R-ohjelmistolla käyttäen paketteja 'lmerTest' (mallien p-arvot), 'performance' (mallien selitysasteet R2) ja 'lme4' (satunnaismallien estimointi).

Tulokset

Vuonna 2022 energiajuomia käytti 26,5 prosenttia 11-vuotiaista, 53,5 prosenttia 13-vuotiaista ja 65 prosenttia 15-vuotiaista (taulukko 2). Ikäryhmien väliset erot tulivat selkeimmin esiin viikoittaiskäytössä, jota raportoi 10,7 prosenttia 11-vuotiaista, 29,3 prosenttia 13-vuotiaista ja 46,5 prosenttia 15-vuotiaista.

Viikoittaiskäyttäjien kohdalla ikäryhmien väliset erot korostuivat erityisesti useammin kuin kerran viikossa käyttävillä; 11-vuotiaista heitä oli 6,7 prosenttia ja 13- ja 15-vuotiaista 19,7 prosenttia ja 33,7 prosenttia. Sukupuolten välinen ero havaittiin vain 11-vuotiailla: pojilla kulutus oli yleisempää kuin tytöillä.

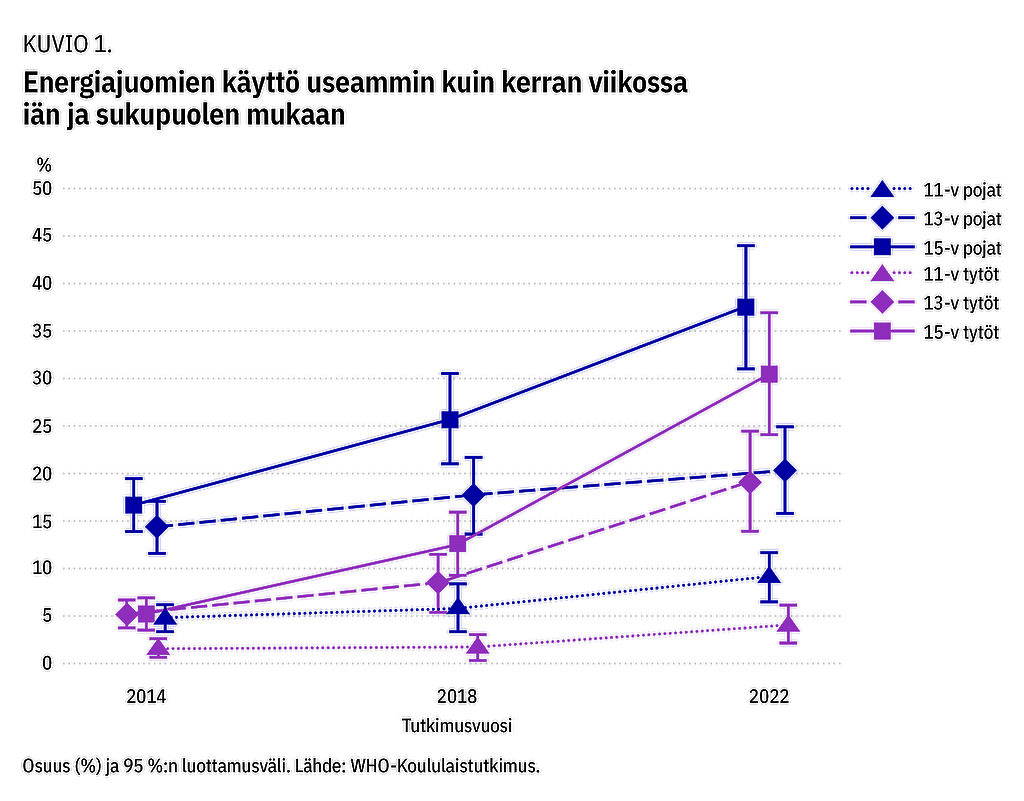

Energiajuomien käyttö yleistyi vuosien 2014 (35,7 prosenttia), 2018 (40,2 prosenttia) ja 2022 (48,6 prosenttia) välillä. Ajallisen muutoksen tarkastelu iän mukaan osoitti, että vuodesta 2014 vuoteen 2022 tultaessa useammin kuin kerran viikossa energiajuomia käyttävien 11- ja 13-vuotiaiden osuudet kaksinkertaistuivat. 15-vuotiaiden kohdalla osuus puolestaan kolminkertaistui (kuvio 1). Lisäksi energiajuomia käyttämättömien osuuksissa kehityssuunta oli laskeva kaikissa ikäryhmissä.

Läpi tarkasteluvuosien energiajuomia käyttävien poikien osuus säilyi samana. Käyttäjäryhmien osuuksissa tapahtui kuitenkin muutosta; samalla kun harvemmin kuin viikoittain käyttävien osuus pieneni, useita kertoja viikossa käyttävien osuus kasvoi. Sen sijaan tytöillä osuuksien kasvua tapahtui niin käyttäjien määrässä kuin käyttäjäryhmissä (viikoittain käyttävien ryhmissä).

Kummallakin sukupuolella suurin muutos tapahtui energiajuomien käytössä useammin kuin kerran viikossa; tytöillä osuus yli nelinkertaistui ja pojilla lähes kaksinkertaistui. Kasvu oli suurinta 15-vuotiailla tytöillä, joiden kohdalla energiajuomia useammin kuin kerran viikossa käyttävien osuus kuusinkertaistui.

Tarkasteltaessa samanaikaisesti iän, sukupuolen ja perheen varallisuuden yhteyttä energiajuomien käyttöön useammin kuin kerran viikossa (taulukko 3, malli 1B), havaittiin, että käyttö oli yleisempää vanhemmilla vastaajilla sekä pojilla. Ikäryhmien välinen ero kasvoi vuoteen 2022, mutta sukupuolten välinen ero kaventui.

Perheen varallisuus oli yhteydessä käyttöön vain 2022, jolloin korkeamman varallisuuden perheissä lapset ja nuoret käyttivät energiajuomia muita yleisemmin. Kun tarkasteluun lisättiin suositusten mukainen yöunen pituus, useammin kuin kerran viikossa tapahtuva energiajuomien käyttö oli kaikkina tarkasteluvuosina yleisempää niillä lapsilla ja nuorilla, jotka eivät yltäneet ikäryhmänsä mukaiseen yöunen pituussuositukseen (taulukko 3, malli 2B). Lisäksi iän, sukupuolen ja perheen varallisuuden roolit selittäjinä säilyivät.

Lapset ja nuoret, jotka eivät käyttäneet energiajuomia, olivat läpi tarkasteluvuosien yleisemmin tyttöjä, iältään nuorempia ja nukkuivat suosituksen mukaisesti koulupäivää edeltävänä yönä (taulukko 3, mallit 1A ja 2A). Sukupuolten välinen ero käyttämättömyydessä kaventui tarkasteluvuosien välillä. Vuonna 2022 käyttämättömyyteen oli yhteydessä myös perheen matalampi varallisuus.

Päätelmät

Tutkimuksessa tarkasteltiin 11-, 13- ja 15-vuotiaiden energiajuomien käyttöä ja siihen yhteydessä olevia tekijöitä vuosina 2014, 2018 ja 2022. Tulokset osoittivat huomattavaa kasvua energiajuomien käytössä: voimakkaimmin vuosien 2018 ja 2022 välillä ja erityisesti useita kertoja viikossa käyttävien osuudessa.

Huomioitavaa oli myös, että käyttö ei jakaantunut tasaisesti lasten ja nuorten parissa ja että käytön sosiodemografisten tekijöiden mukaisissa eroissa on tapahtunut muutosta ajassa.

Läpi tarkasteluvuosien energiajuomien käyttö yleistyi iän mukaan. Vaikka kasvu oli voimakkainta vanhimmassa ikäryhmässä, energiajuomien käyttö yleistyi jo alakoulun 11-vuotiailla. Lisäksi vaikka vuonna 2022 suurin osa 11-vuotiaista ei käyttänyt energiajuomia, joka kymmenes käytti niitä säännöllisesti eli viikoittain.

Merkittävää oli myös sukupuolierojen kaventuminen ja perheen varallisuuden roolin vahvistuminen vuoteen 2022 tultaessa. Poikien energiajuomien käyttö niin Suomessa kuin kansainvälisestikin on ollut yleisempää tyttöihin verrattuna vielä vuonna 2018 (6,18) ja ennen sitä (8,18,19,20,21)

Sukupuolten välisen eron kaventuminen selittyy tyttöjen energiajuomien käytön voimakkaammalla yleistymisellä poikiin verrattuna. Sekä tämän tuloksen että ylipäätään energiajuomien käytön yleistymisen taustalla vaikuttanee määrällisesti ja sisällöllisesti muuttunut markkinointi, jonka nuoret raportoivat vaikuttavan heidän energiajuomien käyttöönsä (22,23,24).

Markkinointi tavoittaa nykyään tehokkaammin ja laajemmin lapset ja nuoret sosiaalisen median ja julkisuuden henkilöiden (25), kuten urheilijoiden, kautta. Aiemmin markkinointi kohdistui erityisesti poikia kiinnostaviin teemoihin (6), mutta nykyään se kattaa extreme-urheilun ja videopelien (25) lisäksi esimerkiksi hyvinvointiin, liikkumiseen ja opiskeluun liittyviä sisältöjä.

Tämä monipuolistuminen näkyy nuorten raportoimissa energiajuomien käytön syissä (23,26,27). WHO määrittelee markkinoinnin kaupalliseksi terveyden osatekijäksi (28) ja on kehottanut rajoittamaan energiajuomien markkinointia lapsille ja nuorille (29).

Edellä kuvattu markkinoinnin muutos ei kuitenkaan täysin selittäne sitä, miksi vuonna 2022 energiajuomien käyttö oli yleisempää korkeammasta perheen varallisuudesta raportoivien lasten ja nuorten keskuudessa. Tulos on aiemman tutkimustiedon perusteella yllättävä, sillä korkeampi sosioekonominen asema on tyypillisesti ollut yhteydessä suotuisampaan terveyskäyttäytymiseen, kuten terveellisempään ravitsemukseen (30) – mukaan lukien vähäisempään energiajuomien käyttöön niissä kansainvälisissä tutkimuksissa, joiden aineisto on kerätty ennen vuotta 2020 (19,20,21,31). Myöskään energiajuomien hinnoittelu ei selittäne muutosta, sillä saatavilla on hyvin erihintaisia tuotteita.

Tarkasteltaessa energiajuomien yhteyttä unitottumuksiin, havaittiin aiempien tutkimustulosten (32) mukaisesti, että energiajuomia käyttivät yleisemmin lapset ja nuoret, jotka nukkuivat suosituksia vähemmän.

Lyhyt yöuni voi olla käytön taustalla vaikuttaja tekijä, jolloin lapset ja nuoret voivat käyttää energiajuomia parantaakseen vireyttä ja keskittymistä sekä pysyäkseen hereillä (26,27). Lyhyt yöuni voi olla myös seurausta energiajuomien käytöstä kofeiinin vaikutuksista johtuen.

Sen lisäksi että energiajuomien ja riittämättömän unen välinen yhteys voi olla kaksisuuntainen, niihin yhteydessä olevissa tekijöissä on yhtäläisyyksiä. Riittämätön uni vaikuttaa kognitiivisiin toimintoihin heikentävästi (33), ja on lisäksi yhteydessä eri kardiometabolisiin riskitekijöihin (34) sekä ahdistuneisuuteen (35). Myös energiajuomien sisältämän kofeiinin käytöstä voi seurata ahdistuneisuutta (36). Seurauksena voi olla haitallinen kierre, joka vaikuttaa oppimiseen ja terveyteen.

Terveydenhuollossa unisuositusten toteutumista voidaan käyttää indikaattorina lasten ja nuorten energiajuomien käytön seurannassa. Energiajuomien käyttö tulisi ottaa puheeksi, kun lapsen ja nuoren kanssa hakeudutaan hoitokontaktiin unihäiriöiden tai psykosomaattisen oireilun vuoksi.

Tämä tutkimus antaa viitteitä, että nykyiset kansalliset toimet eivät ole riittäneet hillitsemään suomalaislasten ja -nuorten energiajuomien käytön kasvua. Tutkimuksen tulosten valossa nykyistä kansallista energiajuomien käyttöä koskevaa suositusta – joka rajaa suosituksen ulkopuolelle 15 vuotta täyttäneet ja sitä vanhemmat nuoret – tulisi tarkastella kriittisesti. Se tulisi päivittää vastaamaan Euroopan elintarvikeviranomaisen tieteellistä kannanottoa kofeiinin päivittäisen saannin turvarajasta, joka kaikilla alle 18-vuotiailla on sama painokilokohtainen.

Kannanotossa kuitenkin todetaan, että koska kyseinen turvaraja on johdettu aikuisten tutkimuksista, tarvitaan luotettavan turvallisen saannin raja-arvon määrittämiseksi lapsiin ja nuoriin kohdistettua tutkimusta. On hyvä myös huomioida, että Euroopassa useampi maa on lailla kieltänyt energiajuomien myynnin alle 18-vuotiaille (37,38,39).

Tutkimuksen vahvuuksia ovat kansainvälistä HBSC-tutkimuksen protokollaa (40) hyödyntäen kerätyn aineiston koko ja edustavuus sekä kahdeksan vuoden tarkastelujakso. Tutkimus tuotti ensimmäistä kertaa kansallisesti edustavaa tietoa alakoululaisten energiajuomien käytöstä Suomessa.

Itseraportoitujen tietojen kohdalla yli- tai aliraportointi on mahdollista (41,42,43). Tutkimuksessa ei selvitetty käytön vuorokaudenaikaa tai energiajuomien määrää, eikä poikkileikkausaineisto osoita kausaalisuhteita.

Tutkimus antaa vertailukelpoista tietoa suomalaislasten ja -nuorten energiajuomien käytön kehittymisestä ja sosiodemografisten tekijöiden mukaisista eroista, joita tulee jatkossakin seurata. Energiajuomien käytön yleistymiseen vaikuttavien tekijöiden ymmärtämiseksi tulisi tarkastella käyttötilanteita ja -syitä, joihin kaupalliset tekijät vastaavat.

Säännöllisen energiajuomien ja kofeiinin käytön vaikutuksista hermoston kehitykseen ei ole tarpeeksi tutkimusta. Varhaisella puuttumisella voidaan ehkäistä terveyttä ja hyvinvointia uhkaavien tekijöiden kasaantumista sekä vähentää tulevaisuuden sairastuvuuden taakkaa.

Kirjoittajien ilmoittama käsikirjoitukseen liittyvä rahoitus:

Juho Vainion Säätiö

TABLE 1_ENGLISH TABLE 2_ENGLISH

TABLE 3_ENGLISH

FIGURE1_ENGLISH

Maija Puupponen: Apuraha (Juho Vainion Säätiö).

Markus Kulmala: Palkkiot osallistumisesta tutkimuksen toteutukseen (Jyväskylän yliopisto), korvaus käsikirjoituksen kirjoittamisesta tai tarkistamisesta (Jyväskylän yliopisto).

Raili Välimaa, Jorma Tynjälä, Leena Paakkari: Ei sidonnaisuuksia.

Tämä tiedettiin

• Energiajuomien käyttö on yhteydessä epäsuotuisiin terveysvaikutuksiin ja muuhun haitalliseen terveyskäyttäytymiseen.

• Energiajuomia ei suositella lapsille ja nuorille niiden korkean kofeiinipitoisuuden vuoksi.

• Energiajuomien käyttö on yleisempää pojilla kuin tytöillä.

Tutkimus opetti

• Nykyiset suositukset eivät ole riittäneet hillitsemään lasten ja nuorten energiajuomien käytön kasvua.

• Säännöllistä käyttöä esiintyy jo alakoulun 11-vuotiailla.

• Energiajuomien käyttö on yleisempää niillä lapsilla ja nuorilla, joilla ikäryhmän mukainen yöunen pituussuositus ei täyty.

- 1

- Breda JJ, Whiting SH, Encarnação R ym. Energy drink consumption in Europe: A review of the risks, adverse health effects, and policy options to respond. Front Public Health 2014;2:134. doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2014.00134

- 2

- Ajibo C, Van Griethuysen A, Visram S, Lake AA. Consumption of energy drinks by children and young people: a systematic review examining evidence of physical effects and consumer attitudes. Public Health 2024;227:274–81. doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2023.08.024

- 3

- Kaldenbach S, Leonhardt M, Lien L, Bjærtnes AA, Strand TA, Holten-Andersen MN. Sleep and energy drink consumption among Norwegian adolescents – a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2022;22:534. doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-12972-w

- 4

- Kim DH, Kim B, Lee SG, Kim TH. Poor sleep is associated with energy drinks consumption among Korean adolescents. Public Health Nutr 2023;26:3256–65. doi.org/10.1017/S136898002300191X

- 5

- Kristjansson AL, Sigfusdottir ID, Mann MJ, James JE. Caffeinated sugar-sweetened beverages and common physical complaints in Icelandic children aged 10–12years. Prev Med 2014;58:40–4. doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.10.011

- 6

- Nuss T, Morley B, Scully M, Wakefield M. Energy drink consumption among Australian adolescents associated with a cluster of unhealthy dietary behaviours and short sleep duration. Nutr J 2021;20:64. doi.org/10.1186/s12937-021-00719-z

- 7

- Puupponen M, Tynjälä J, Välimaa R, Paakkari L. Associations between adolescents’ energy drink consumption frequency and several negative health indicators. BMC Public Health 2023;23:258. doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15055-6

- 8

- Koivusilta L, Kuoppamäki H, Rimpelä A. Energy drink consumption, health complaints and late bedtime among young adolescents. Int J Public Health 2016;61:299–306. doi.org/10.1007/s00038-016-0797-9

- 9

- Schneider MB, Benjamin HJ, Committee on Nutrition and the Council on Sports Medicine and Fitness. Sports drinks and energy drinks for children and adolescents: Are they appropriate? Pediatrics 2011;127:1182–9. doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-0965

- 10

- EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (NDA). Scientific Opinion on the safety of caffeine. EFS2 2015;13. doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2015.4102

- 11

- THL. Syödään yhdessä -ruokasuositukset lapsiperheille 2019. 2. uudistettu painos. Helsinki 2019. (siteerattu 12.9.2024). urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-343-254-3

- 12

- Valsta L, Borg P, Heiskanen S ym. Juomat ravitsemuksessa. (siteerattu 14.9.2024). Valtion ravitsemusneuvottelukunnan raportti 2008. www.ruokavirasto.fi/globalassets/teemat/terveytta-edistava-ruokavalio/kuluttaja-ja-ammattilaismateriaali/julkaisut/juomat_ravitsemuksessa.pdf

- 13

- Ojala K, Puupponen M. Ruokatottumukset. Kirjassa: Ojala K, Kulmala M, toim. Koululaisten terveys ja muuttuvat haasteet 2022 – WHO-Koululaistutkimus 40 vuotta (Schoolchildren’s health and changing challenges 2022 – HBSC Finland 40 years)., Jyväskylän yliopisto 2023. doi.org/10.17011/jyureports/2023/25

- 14

- Zucconi S, Volpato C, Adinolfi F ym. Gathering consumption data on specific consumer groups of energy drinks. EFSA Supporting Publications 2013;10:394E. doi.org/10.2903/sp.efsa.2013.EN-394

- 15

- Hirshkowitz M, Whiton K, Albert SM ym. National Sleep Foundation’s updated sleep duration recommendations: final report. Sleep Health 2015;1:233–43. doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2015.10.004

- 16

- Nadeem IM, Shanmugaraj A, Sakha S, Horner NS, Ayeni OR, Khan M. Energy drinks and their adverse health effects: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Health 2021;13:265–77. doi.org/10.1177/1941738120949181

- 17

- Nakagawa S, Johnson PCD, Schielzeth H. The coefficient of determination R2 and intra-class correlation coefficient from generalized linear mixed-effects models revisited and expanded. J R Soc Interface 2017;14:20170213. doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2017.0213

- 18

- Puupponen M, Tynjälä J, Tolvanen A, Välimaa R, Paakkari L. Energy drink consumption among finnish adolescents: prevalence, associated background factors, individual resources, and family factors. Int J Public Health 2021;66:620268. doi.org/10.3389/ijph.2021.620268

- 19

- Degirmenci N, Fossum IN, Strand TA, Vaktskjold A, Holten-Andersen MN. Consumption of energy drinks among adolescents in Norway: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2018;18:1391. doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6236-5

- 20

- Frayon S, Wattelez G, Cherrier S, Cavaloc Y, Lerrant Y, Galy O. Energy drink consumption in a pluri-ethnic population of adolescents in the Pacific. PLOS One 2019;14. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0214420.

- 21

- Holubcikova J, Kolarcik P, Madarasova Geckova A, Reijneveld SA, van Dijk JP. Regular energy drink consumption is associated with the risk of health and behavioural problems in adolescents. Eur J Pediatr 2017;176:599–605. doi.org/10.1007/s00431-017-2881-4

- 22

- Bunting H, Baggett A, Grigor J. Adolescent and young adult perceptions of caffeinated energy drinks. A qualitative approach. Appetite 2013;65:132–8. doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2013.02.011.

- 23

- Maloney EK, Bleakley A, Stevens R, Ellithorpe M, Jordan A. Urban youth perceptions of sports and energy drinks: Insights for health promotion messaging. Health Educ J 2023;82:324–35. doi.org/10.1177/00178969231157699

- 24

- Visram S, Crossley SJ, Cheetham M, Lake A. Children and young people’s perceptions of energy drinks: A qualitative study. PLOS One 2017;12:e0188668. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0188668

- 25

- Ayoub C, Pritchard M, Bagnato M, Remedios L, Potvin Kent M. The extent of energy drink marketing on Canadian social media. BMC Public Health 2023;23:767. doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15437-w

- 26

- Kaldenbach S, Strand T, Holten-Andersen M. Experiences with energy drink consumption among Norwegian adolescents. J Nutr Sci 2023;12. doi.org/10.1017/jns.2023.17

- 27

- Luo R, Fu R, Dong L ym. Knowledge and prevalence of energy drinks consumption in Shanghai, China: a cross-sectional survey of adolescents. Gen Psych 2021;34:e100389. doi.org/10.1136/gpsych-2020-100389

- 28

- WHO. Commercial determinants of health (päivitetty 21.3.2023). www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/commercial-determinants-of-health

- 29

- WHO Regional Office for Europe nutrient profile model: second edition. (siteerattu 10.8.2024). Kööpenhamina: WHO Regional Office for Europe 2023. iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/366328/WHO-EURO-2023-6894-46660-68492-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- 30

- Poulain T, Vogel M, Sobek C, Hilbert A, Körner A, Kiess W. Associations between socio-economic status and child health: findings of a large German cohort study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16:677. doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16050677

- 31

- Utter J, Denny S, Teevale T, Sheridan J. Energy drink consumption among New Zealand adolescents: Associations with mental health, health risk behaviours and body size: Energy drinks and adolescent health. J Paediatr Child Health 2017;54. doi.org/10.1111/jpc.13708

- 32

- Sampasa-Kanyinga H, Hamilton HA, Chaput J-P. Sleep duration and consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and energy drinks among adolescents. Nutrition 2018;48:77–81. doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2017.11.013

- 33

- Short MA, Blunden S, Rigney G ym. Cognition and objectively measured sleep duration in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Health 2018;4:292–300. doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2018.02.004.

- 34

- Quist JS, Sjödin A, Chaput J-P, Hjorth MF. Sleep and cardiometabolic risk in children and adolescents. Sleep Med Rev 2016;29:76–100. doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2015.09.001

- 35

- Roberts RE, Duong HT. Is there an association between short sleep duration and adolescent anxiety disorders? Sleep Med 2017;30:82–7. doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2016.02.007

- 36

- Meltzer HM, Fotland TØ, Alexander J ym. Risk assessment of caffeine among children and adolescents in the Nordic countries. Nordic Council of Ministers 2008. doi.org/10.6027/tn2008-551

- 37

- Puolan parlamentin alahuone Sejm, Amendment to the Public Health Act, 17.8.2023. orka.sejm.gov.pl/proc9.nsf/ustawy/3258_u.htm

- 38

- Latvian parlamentti Saeima, Law on the Handling of Energy Drinks, 1.6.2016. likumi.lv/ta/id/280078-energijas-dzerienu-aprites-likums

- 39

- Liettuan parlamentti Seima, Law on Food No. XII-885, 15.5.2014. e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalActPrint/lt?jfwid=tu0odnswn&documentId=daaa9dd2df4c11e3a0be833418c290fb&category=TAD

- 40

- Inchley J, Currie D, Samdal O, Jåstad A, Cosma A, Nic Gabhainn S, toim. Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study protocol: background, methodology and mandatory items for the 2021/22 survey. Glasgow: MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit, University of Glasgow 2023.

- 41

- Vereecken CA, Rossi S, Giacchi MV, Maes L. Comparison of a short food-frequency questionnaire and derived indices with a seven-day diet record in Belgian and Italian children. Int J Public Health 2008;53:297–305. doi.org/10.1007/s00038-008-7101-6

- 42

- Vereecken CA, Maes L. A Belgian study on the reliability and relative validity of the Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children food-frequency questionnaire. Public Health Nutr 2003;6:581–8. doi.org/10.1079/PHN2003466

- 43

- Wong JE, Parnell WR, Black KE, Skidmore PM. Reliability and relative validity of a food frequency questionnaire to assess food group intakes in New Zealand adolescents. Nutr J 2012;11:65. doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-11-65

- 44

- Hartley, JEK, Levin, K, and Currie, C. A new version of the HBSC family affluence scale – FAS III: Scottish qualitative findings from the international FAS development study. Child Ind Res 2016;9:233–45. doi.org/10.1007/s12187-015-9325-3

- 45

- Torsheim T, Cavallo F, Levin KA ym. Psychometric validation of the revised family affluence scale: a latent variable approach. Child Indic Res 2016;9:771–84. doi.org/10.1007/s12187-015-9339-x

Increased consumption of energy drinks among children and adolescents between 2014 and 2022 is associated with non-adherence to sleep duration recommendations

Background There is a lack of monitoring data on energy drink consumption by Finnish children and adolescents, despite the associated adverse health effects. Energy drinks are not recommended for children and adolescents, due especially to their high caffeine content.

Methods The nationally representative data are based on the HBSC study conducted in 2014, 2018, and 2022 (n = 15 171). Descriptive analyses and logistic mixed models were used to examine energy drink consumption among 11-, 13-, and 15-year-olds, its changes over time, and the associations with sociodemographic factors and adherence to sleep recommendations.

Results From 2014 to 2022, the consumption of energy drinks increased across all age groups, with a notable rise in frequent use (more than once a week). The differences between age groups widened, while the gender gap narrowed. Consumption was more prevalent among adolescents who did not meet the recommended sleep duration for their age group. In 2022, consumption was also more prevalent among those with higher family affluence.

Conclusions There has been a rise in the consumption rates of energy drinks among children and adolescents. More information on energy drink consumption is needed to promote healthy lifestyles, evaluate the effectiveness of current actions, and inform health policy.

The consumption of energy drinks among children and adolescents has been noted as a potential public health threat (11 Breda JJ, Whiting SH, Encarnação R ym. Energy drink consumption in Europe: A review of the risks, adverse health effects, and policy options to respond. Front Public Health 2014;2:134. doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2014.00134) and is associated with a number of adverse health effects. These include cardiovascular symptoms, such as increased blood pressure, changes in heart rate, and palpitations) (22 Ajibo C, Van Griethuysen A, Visram S, Lake AA. Consumption of energy drinks by children and young people: a systematic review examining evidence of physical effects and consumer attitudes. Public Health 2024;227:274–81. doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2023.08.024). There is also evidence of sleep disturbances, including short sleep duration (33 Kaldenbach S, Leonhardt M, Lien L, Bjærtnes AA, Strand TA, Holten-Andersen MN. Sleep and energy drink consumption among Norwegian adolescents – a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2022;22:534. doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-12972-w,44 Kim DH, Kim B, Lee SG, Kim TH. Poor sleep is associated with energy drinks consumption among Korean adolescents. Public Health Nutr 2023;26:3256–65. doi.org/10.1017/S136898002300191X,55 Kristjansson AL, Sigfusdottir ID, Mann MJ, James JE. Caffeinated sugar-sweetened beverages and common physical complaints in Icelandic children aged 10–12years. Prev Med 2014;58:40–4. doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.10.011,66 Nuss T, Morley B, Scully M, Wakefield M. Energy drink consumption among Australian adolescents associated with a cluster of unhealthy dietary behaviours and short sleep duration. Nutr J 2021;20:64. doi.org/10.1186/s12937-021-00719-z,77 Puupponen M, Tynjälä J, Välimaa R, Paakkari L. Associations between adolescents’ energy drink consumption frequency and several negative health indicators. BMC Public Health 2023;23:258. doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15055-6) and late bedtime or night-time awakenings (88 Koivusilta L, Kuoppamäki H, Rimpelä A. Energy drink consumption, health complaints and late bedtime among young adolescents. Int J Public Health 2016;61:299–306. doi.org/10.1007/s00038-016-0797-9), in addition to various psychological and somatic symptoms (22 Ajibo C, Van Griethuysen A, Visram S, Lake AA. Consumption of energy drinks by children and young people: a systematic review examining evidence of physical effects and consumer attitudes. Public Health 2024;227:274–81. doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2023.08.024,55 Kristjansson AL, Sigfusdottir ID, Mann MJ, James JE. Caffeinated sugar-sweetened beverages and common physical complaints in Icelandic children aged 10–12years. Prev Med 2014;58:40–4. doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.10.011,88 Koivusilta L, Kuoppamäki H, Rimpelä A. Energy drink consumption, health complaints and late bedtime among young adolescents. Int J Public Health 2016;61:299–306. doi.org/10.1007/s00038-016-0797-9), and poor self-rated health (77 Puupponen M, Tynjälä J, Välimaa R, Paakkari L. Associations between adolescents’ energy drink consumption frequency and several negative health indicators. BMC Public Health 2023;23:258. doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15055-6). These effects are particularly related to the high caffeine content of energy drinks (99 Schneider MB, Benjamin HJ, Committee on Nutrition and the Council on Sports Medicine and Fitness. Sports drinks and energy drinks for children and adolescents: Are they appropriate? Pediatrics 2011;127:1182–9. doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-0965), for which no safe intake limit has been reliably established for this population group (1010 EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (NDA). Scientific Opinion on the safety of caffeine. EFS2 2015;13. doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2015.4102).

In Finland, efforts have been made to curb the consumption of energy drinks through recommendations from The National Nutrition Council of Finland and the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare. The recommendations apply to persons under 15 years of age (1111 THL. Syödään yhdessä -ruokasuositukset lapsiperheille 2019. 2. uudistettu painos. Helsinki 2019. (siteerattu 12.9.2024). urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-343-254-3,1212 Valsta L, Borg P, Heiskanen S ym. Juomat ravitsemuksessa. (siteerattu 14.9.2024). Valtion ravitsemusneuvottelukunnan raportti 2008. www.ruokavirasto.fi/globalassets/teemat/terveytta-edistava-ruokavalio/kuluttaja-ja-ammattilaismateriaali/julkaisut/juomat_ravitsemuksessa.pdf). Despite the recommendations, the consumption of energy drinks is common: in 2022, only around 50% of adolescents aged 13 and 15 reported non-consumption of energy drinks (1313 Ojala K, Puupponen M. Ruokatottumukset. Kirjassa: Ojala K, Kulmala M, toim. Koululaisten terveys ja muuttuvat haasteet 2022 – WHO-Koululaistutkimus 40 vuotta (Schoolchildren’s health and changing challenges 2022 – HBSC Finland 40 years)., Jyväskylän yliopisto 2023. doi.org/10.17011/jyureports/2023/25).

Already in 2013, the European Food Safety Authority recommended monitoring the increase in energy drink consumption (1414 Zucconi S, Volpato C, Adinolfi F ym. Gathering consumption data on specific consumer groups of energy drinks. EFSA Supporting Publications 2013;10:394E. doi.org/10.2903/sp.efsa.2013.EN-394). However, there have been only limited monitoring data in Finland on the prevalence of energy drink consumption among children and adolescents and the factors associated with their consumption, with a particular lack of data for children in primary education. The present study examined the consumption of energy drinks among persons aged 11, 13, and 15 in the years 2014, 2018, and 2022. It also examined the associations between energy drink consumption and age, gender, family affluence, and adherence to age-specific night sleep duration recommendations (1515 Hirshkowitz M, Whiton K, Albert SM ym. National Sleep Foundation’s updated sleep duration recommendations: final report. Sleep Health 2015;1:233–43. doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2015.10.004), and considered whether these associations had changed over the years. The association between sleep duration and energy drink consumption was examined because of a previously observed mutual connection – one that had been noticed, but had received little attention at national level (77 Puupponen M, Tynjälä J, Välimaa R, Paakkari L. Associations between adolescents’ energy drink consumption frequency and several negative health indicators. BMC Public Health 2023;23:258. doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15055-6,88 Koivusilta L, Kuoppamäki H, Rimpelä A. Energy drink consumption, health complaints and late bedtime among young adolescents. Int J Public Health 2016;61:299–306. doi.org/10.1007/s00038-016-0797-9,1616 Nadeem IM, Shanmugaraj A, Sakha S, Horner NS, Ayeni OR, Khan M. Energy drinks and their adverse health effects: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Health 2021;13:265–77. doi.org/10.1177/1941738120949181).

Methods

The cross-sectional data of the study consisted of the nationally representative WHO School Health Survey (HBSC study) questionnaire data from the years 2014, 2018, and 2022 (N = 15 171; boys 50.2%; annual variation in respondents’ N = 3408–7925). The study data cover 11-, 13-, and 15-year-olds, representing the 5th, 7th, and 9th grade levels.

The sampling was conducted separately for each data collection year using the school register maintained by Statistics Finland. Participating schools were selected via stratified cluster sampling to ensure geographical and residential area representativeness. The sampling unit was the school, with the selection probability proportional to its size, and the participating classes within the sampled schools were randomly selected. The 2014 data were collected using paper questionnaires, while the 2018 and 2022 data were collected electronically using the Webropol survey program. Participation in the study was voluntary, and the questionnaire was answered anonymously. In addition to age and self-reported gender, the study used the variables described in Table 1. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata (version 18) statistical software; thus, the weighted percentages, corrected for sampling method, were calculated, along with their 95% confidence intervals for energy drink consumption across different background variables (Table 2). Two different models were fitted in the regression models, considering each year separately (Table 3). The first models accounted for age, gender, and family wealth. The second models included also the recommended night sleep duration. For 2018, the second model did not include 11-year-olds, as sleep duration was not asked of them at that time. The models accounted for clustering at the school level using a random effect. The regression estimates of the models could be compared across the years by examining the intersections of the 95% confidence intervals. The continuous variables in the models were standardized by mean and standard deviation. In addition, both marginal and conditional R2 values were calculated for the models (1717 Nakagawa S, Johnson PCD, Schielzeth H. The coefficient of determination R2 and intra-class correlation coefficient from generalized linear mixed-effects models revisited and expanded. J R Soc Interface 2017;14:20170213. doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2017.0213). In the mixed models, marginal R2 refers to the explanatory power when only the predictor variables are considered, while conditional R2 also accounts for the random effect at the school level. The regression models were created using R software with the packages 'lmerTest' (model p-values), 'performance' (model explanatory power R2), and 'lme4' (random model estimation).

Results

In 2022, 26.5% of 11-year-olds, 53.5% of 13-year-olds, and 65% of 15-year-olds consumed energy drinks (Table 2). The differences between age groups were evident in weekly consumption, reported by 10.7% of 11-year-olds, 29.3% of 13-year-olds, and 46.5% of 15-year-olds. Furthermore, there were particularly pronounced differences between age groups regarding those consuming energy drinks more-than-once-a-week: 6.7% of 11-year-olds, 19.7% of 13-year-olds, and 33.7% of 15-year-olds. A gender difference was observed only among 11-year-olds, with boys consuming more than girls.

The consumption of energy drinks increased between 2014 (35.7%), 2018 (40.2%), and 2022 (48.6%). An examination of the temporal change in relation to age showed that from 2014 to 2022, the proportions of 11- and 13-year-olds consuming energy drinks more than once a week doubled, and for 15-year-olds, it tripled (Figure 1). Furthermore, the trend in the proportions of those not consuming energy drinks showed a decrease in all the age groups.

Throughout the study years, the proportion of boys consuming energy drinks remained the same. However, there were changes in the consumer groups; hence, while the proportion of those in the less-than-weekly category decreased, the proportion of those consuming more than once a week increased. In contrast, among girls, there was an increase in both the number of consumers overall and the consumer groups (weekly consumers). The most significant change for both genders occurred in the consumption of energy drinks more than once a week: among girls, the proportion more than quadrupled, and among boys, it almost doubled. The growth was greatest among 15-year-old girls, with the proportion of those consuming energy drinks more than once a week increasing sixfold.

Through simultaneous examination of the associations between age, gender, and family affluence and the consumption of energy drinks more than once a week (Table 3, Model 1B), it was found that consumption was more common among older respondents and boys. By 2022, the difference between the age groups had increased, but the gender difference had narrowed. Family affluence was associated with consumption only in 2022, with children and adolescents from higher affluence families consuming energy drinks more frequently than others. When recommended sleep duration was added to the analysis, it was found that in all the study years, more-than-once-a-week consumption of energy drinks was more common among children and adolescents who did not meet the age-specific night sleep duration recommendations (Table 3, Model 2B). Furthermore, the roles of age, gender, and family affluence as explanatory factors remained.

Over the years of 2014, 2018 and 2022, children and adolescents who did not consume energy drinks tended to be girls, younger in age, and to sleep the night before a school day in line with the recommendation (Table 3, Models 1A and 2A). The gender difference in non-consumption narrowed over the study years. Interestingly, in 2022, non-consumption was associated with lower rather than higher family affluence.

Discussion

The study examined the consumption of energy drinks among 11-, 13-, and 15-year-olds and the factors associated with it in the years 2014, 2018, and 2022. The results showed a significant increase in the consumption of energy drinks, most notably between 2018 and 2022, and particularly in the proportion of those consuming the drinks more than once a week. It was also noteworthy that consumption was not evenly distributed among children and adolescents, and that differences have occurred over time in relation to sociodemographic factors.

Over the study years 2014, 2018 and 2022, the consumption of energy drinks increased with age. Although the growth was strongest in the oldest age group, the consumption of energy drinks also became more common among 11-year-olds in primary education. Furthermore, while in 2022 the majority of 11-year-olds did not consume energy drinks, one in ten used them regularly, i.e. weekly. It was also notable that by 2022 the gender differences had narrowed and the role of family affluence strengthened. Thus, both in Finland and internationally, the consumption of energy drinks had been more common among boys than among girls, both in 2018 (66 Nuss T, Morley B, Scully M, Wakefield M. Energy drink consumption among Australian adolescents associated with a cluster of unhealthy dietary behaviours and short sleep duration. Nutr J 2021;20:64. doi.org/10.1186/s12937-021-00719-z,1818 Puupponen M, Tynjälä J, Tolvanen A, Välimaa R, Paakkari L. Energy drink consumption among finnish adolescents: prevalence, associated background factors, individual resources, and family factors. Int J Public Health 2021;66:620268. doi.org/10.3389/ijph.2021.620268) and prior to that (88 Koivusilta L, Kuoppamäki H, Rimpelä A. Energy drink consumption, health complaints and late bedtime among young adolescents. Int J Public Health 2016;61:299–306. doi.org/10.1007/s00038-016-0797-9,1818 Puupponen M, Tynjälä J, Tolvanen A, Välimaa R, Paakkari L. Energy drink consumption among finnish adolescents: prevalence, associated background factors, individual resources, and family factors. Int J Public Health 2021;66:620268. doi.org/10.3389/ijph.2021.620268,1919 Degirmenci N, Fossum IN, Strand TA, Vaktskjold A, Holten-Andersen MN. Consumption of energy drinks among adolescents in Norway: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2018;18:1391. doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6236-5,2020 Frayon S, Wattelez G, Cherrier S, Cavaloc Y, Lerrant Y, Galy O. Energy drink consumption in a pluri-ethnic population of adolescents in the Pacific. PLOS One 2019;14. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0214420.,2121 Holubcikova J, Kolarcik P, Madarasova Geckova A, Reijneveld SA, van Dijk JP. Regular energy drink consumption is associated with the risk of health and behavioural problems in adolescents. Eur J Pediatr 2017;176:599–605. doi.org/10.1007/s00431-017-2881-4). The narrowing of the gender gap can be explained by the greater increase in the consumption of energy drinks among girls relative to boys. It seems likely that this result and also the overall increase in the consumption of energy drinks are influenced by changes in marketing, both in quantity and content, given that young people report this aspect as affecting their consumption of energy drinks (2222 Bunting H, Baggett A, Grigor J. Adolescent and young adult perceptions of caffeinated energy drinks. A qualitative approach. Appetite 2013;65:132–8. doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2013.02.011.,2323 Maloney EK, Bleakley A, Stevens R, Ellithorpe M, Jordan A. Urban youth perceptions of sports and energy drinks: Insights for health promotion messaging. Health Educ J 2023;82:324–35. doi.org/10.1177/00178969231157699,2424 Visram S, Crossley SJ, Cheetham M, Lake A. Children and young people’s perceptions of energy drinks: A qualitative study. PLOS One 2017;12:e0188668. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0188668). Marketing now reaches children and adolescents more effectively through social media and via public figures (2525 Ayoub C, Pritchard M, Bagnato M, Remedios L, Potvin Kent M. The extent of energy drink marketing on Canadian social media. BMC Public Health 2023;23:767. doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15437-w) such as athletes. Previously, marketing was particularly targeted at themes viewed as interesting to boys (66 Nuss T, Morley B, Scully M, Wakefield M. Energy drink consumption among Australian adolescents associated with a cluster of unhealthy dietary behaviours and short sleep duration. Nutr J 2021;20:64. doi.org/10.1186/s12937-021-00719-z), but it now includes content related to wellbeing, exercise, and studying, in addition to extreme sports and video games (2525 Ayoub C, Pritchard M, Bagnato M, Remedios L, Potvin Kent M. The extent of energy drink marketing on Canadian social media. BMC Public Health 2023;23:767. doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15437-w). This diversification is reflected in the reasons young people report for using energy drinks (2323 Maloney EK, Bleakley A, Stevens R, Ellithorpe M, Jordan A. Urban youth perceptions of sports and energy drinks: Insights for health promotion messaging. Health Educ J 2023;82:324–35. doi.org/10.1177/00178969231157699,2626 Kaldenbach S, Strand T, Holten-Andersen M. Experiences with energy drink consumption among Norwegian adolescents. J Nutr Sci 2023;12. doi.org/10.1017/jns.2023.17,2727 Luo R, Fu R, Dong L ym. Knowledge and prevalence of energy drinks consumption in Shanghai, China: a cross-sectional survey of adolescents. Gen Psych 2021;34:e100389. doi.org/10.1136/gpsych-2020-100389). The WHO defines marketing as a commercial determinant of health (2828 WHO. Commercial determinants of health (päivitetty 21.3.2023). www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/commercial-determinants-of-health) and has urged the restriction of energy drink marketing to children and adolescents (2929 WHO Regional Office for Europe nutrient profile model: second edition. (siteerattu 10.8.2024). Kööpenhamina: WHO Regional Office for Europe 2023. iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/366328/WHO-EURO-2023-6894-46660-68492-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y).

The marketing changes mentioned above do not fully explain why in 2022 the consumption of energy drinks was more common among children and adolescents reporting higher family affluence. This result is surprising, bearing in mind previous research indicating that higher socioeconomic status is associated with more favourable health behaviours, such as healthier nutrition (3030 Poulain T, Vogel M, Sobek C, Hilbert A, Körner A, Kiess W. Associations between socio-economic status and child health: findings of a large German cohort study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16:677. doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16050677). This association was supported by international studies with data collected prior to 2020 (1919 Degirmenci N, Fossum IN, Strand TA, Vaktskjold A, Holten-Andersen MN. Consumption of energy drinks among adolescents in Norway: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2018;18:1391. doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6236-5,2020 Frayon S, Wattelez G, Cherrier S, Cavaloc Y, Lerrant Y, Galy O. Energy drink consumption in a pluri-ethnic population of adolescents in the Pacific. PLOS One 2019;14. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0214420.,2121 Holubcikova J, Kolarcik P, Madarasova Geckova A, Reijneveld SA, van Dijk JP. Regular energy drink consumption is associated with the risk of health and behavioural problems in adolescents. Eur J Pediatr 2017;176:599–605. doi.org/10.1007/s00431-017-2881-4,3131 Utter J, Denny S, Teevale T, Sheridan J. Energy drink consumption among New Zealand adolescents: Associations with mental health, health risk behaviours and body size: Energy drinks and adolescent health. J Paediatr Child Health 2017;54. doi.org/10.1111/jpc.13708), indicating lower consumption of energy drinks in families with higher affluence. Nor does the pricing of energy drinks explain the change, since the products available cover a very wide price range.

It is notable that, in line with previous research (3232 Sampasa-Kanyinga H, Hamilton HA, Chaput J-P. Sleep duration and consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and energy drinks among adolescents. Nutrition 2018;48:77–81. doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2017.11.013), the present study found that children and adolescents who consumed energy drinks had less than the recommended duration of sleep. In fact, short sleep duration could be one factor underlying consumption, insofar as children and adolescents may consume energy drinks to improve alertness and concentration, and stay awake (2626 Kaldenbach S, Strand T, Holten-Andersen M. Experiences with energy drink consumption among Norwegian adolescents. J Nutr Sci 2023;12. doi.org/10.1017/jns.2023.17,2727 Luo R, Fu R, Dong L ym. Knowledge and prevalence of energy drinks consumption in Shanghai, China: a cross-sectional survey of adolescents. Gen Psych 2021;34:e100389. doi.org/10.1136/gpsych-2020-100389). Note further that short night sleep can also be a consequence of energy drink consumption due to the effects of caffeine. One can thus identify a possible bidirectional relationship between energy drink consumption and insufficient sleep, along with similarities in the factors associated with them. Insufficient sleep negatively affects cognitive functions (3333 Short MA, Blunden S, Rigney G ym. Cognition and objectively measured sleep duration in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Health 2018;4:292–300. doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2018.02.004.) and is also associated with various cardiometabolic risk factors (3434 Quist JS, Sjödin A, Chaput J-P, Hjorth MF. Sleep and cardiometabolic risk in children and adolescents. Sleep Med Rev 2016;29:76–100. doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2015.09.001) and anxiety (3535 Roberts RE, Duong HT. Is there an association between short sleep duration and adolescent anxiety disorders? Sleep Med 2017;30:82–7. doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2016.02.007). The use of caffeine in energy drinks can lead to anxiety (3636 Meltzer HM, Fotland TØ, Alexander J ym. Risk assessment of caffeine among children and adolescents in the Nordic countries. Nordic Council of Ministers 2008. doi.org/10.6027/tn2008-551), leading to a harmful cycle affecting learning and health. Overall, in healthcare situations, it would be reasonable to use adherence to sleep recommendations as an indicator in monitoring the consumption of energy drinks among children and adolescents. Furthermore, the consumption of energy drinks should be addressed when medical contact is made regarding sleep disorders or psychosomatic symptoms in children and adolescents.

This study suggests that current national measures have been insufficient to curb the increase in energy drink consumption among Finnish children and adolescents. In the light of the present study, the current national recommendation on energy drink consumption – which excludes persons aged 15 and older – should be updated in line with the opinion of the European Food Safety Authority regarding the safe daily intake limit of caffeine. This, it should be noted, defines the same intake per kilogram of body weight for all individuals, from 1 to 18 years of age. However, the opinion further states that since this limit is derived from adult studies, research on children and adolescents is needed to determine a safe intake limit. It is also worth noting that several European countries have legally banned the sale of energy drinks to persons under 18 (3737 Puolan parlamentin alahuone Sejm, Amendment to the Public Health Act, 17.8.2023. orka.sejm.gov.pl/proc9.nsf/ustawy/3258_u.htm,3838 Latvian parlamentti Saeima, Law on the Handling of Energy Drinks, 1.6.2016. likumi.lv/ta/id/280078-energijas-dzerienu-aprites-likums,3939 Liettuan parlamentti Seima, Law on Food No. XII-885, 15.5.2014. e-seimas.lrs.lt/portal/legalActPrint/lt?jfwid=tu0odnswn&documentId=daaa9dd2df4c11e3a0be833418c290fb&category=TAD).

The strengths of the study include the size and representativeness of the data collected – here adhering to the international HBSC study protocol (4040 Inchley J, Currie D, Samdal O, Jåstad A, Cosma A, Nic Gabhainn S, toim. Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study protocol: background, methodology and mandatory items for the 2021/22 survey. Glasgow: MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit, University of Glasgow 2023.) – and the eight-year observation period. This is the first study to provide nationally representative data on the consumption of energy drinks among children in primary education in Finland. However, over- or under-reporting is possible with self-reported data (4141 Vereecken CA, Rossi S, Giacchi MV, Maes L. Comparison of a short food-frequency questionnaire and derived indices with a seven-day diet record in Belgian and Italian children. Int J Public Health 2008;53:297–305. doi.org/10.1007/s00038-008-7101-6,4242 Vereecken CA, Maes L. A Belgian study on the reliability and relative validity of the Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children food-frequency questionnaire. Public Health Nutr 2003;6:581–8. doi.org/10.1079/PHN2003466,4343 Wong JE, Parnell WR, Black KE, Skidmore PM. Reliability and relative validity of a food frequency questionnaire to assess food group intakes in New Zealand adolescents. Nutr J 2012;11:65. doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-11-65). Moreover, the study did not investigate the time of day or the actual quantity of energy drinks consumed. Nor were the cross-sectional data able to indicate causal relationships.

The study provides comparable information on the development of energy drink consumption among Finnish children and adolescents and the differences according to sociodemographic factors. These should continue to be monitored. To understand the factors influencing the increase in energy drink consumption, it is necessary to examine the situations and reasons for consumption, since these underlie the commercial success of the products in question. Further research should also examine in detail the effects of regular energy drink consumption and caffeine use on nervous system development. It is highly likely that early intervention could prevent the accumulation of factors threatening health and wellbeing and reduce the future burden of morbidity.

This was known

• The consumption of energy drinks is associated with adverse health effects and other harmful health behaviours.

• Energy drinks are not recommended for children and adolescents, due to their high caffeine content.

• The consumption of energy drinks is more common among boys than among girls.

The study taught

• Current recommendations have been insufficient to curb the increase in energy drink consumption among children and adolescents.

• Regular consumption is already present among 11-year-olds in primary education.

• The consumption of energy drinks is more common among children and adolescents who do not meet the age-specific night sleep duration recommendation.

Maija Puupponen, Markus Kulmala, Raili Välimaa, Jorma Tynjälä, Leena Paakkari

University of Jyväskylä, Finland